Irish Workhouse, published 1901, artist unknown

“Careful, or you’ll end up in the poorhouse.”

“That kind of move will land you in the poorhouse.”

“The Poorhouse.” It’s an expression that’s part of our everyday vernacular, and self-explanatory at that. But there was a time when the threat of landing in the poorhouse wasn’t just a metaphor for being broke. To the people of Ireland who lived during the great potato famine of the mid-1800s, the poorhouse was a very real place and the prospect of ending up there a very scary one. The alternative, starvation, was clearly worse, but until recently when I visited a restored, repurposed poorhouse in the small town of Carrickmacross, Ireland, I had no idea how bad the circumstances were that necessitated the building of these workhouses.

Chalk it up to my generation, or my lack of knowledge of Irish history, but one thing is certain: after my visit to Carrickmacross Workhouse, I have a whole new appreciation for this period of Irish history and the generations who were affected by it.

Carrickmacross Workhouse

Carrickmacross Workhouse, restored in 1990

“Workhouse” or “Poorhouse”, the distinction was irrelevant, since when it came to institutions such as Carrickmacross, the terms were interchangeable. One hundred and thirty of these compounds were built by the [then ruling] British government to house starving families in Ireland following the Great Potato Famine of the 1840s that left almost 3 million people destitute. But this was not simple charity: residents were required to work in exchange for shelter and food. And the atmosphere was more like a prison than a residence.

Desperate families across Ireland applied for acceptance, but once approved, men and women were separated from each other with little or no contact. Dormitories, courtyards and dining halls were segregated by gender, and only children under two were allowed to stay with their mothers.

Poorhouses were fenced and workers lived segregated by gender like inmates

Crowded into communal dorms with rudimentary facilities, and doled out meagre rations, death tolls continued to rise even in these facilities, as workhouses began bursting at the seams as Ireland’s destitute grew in numbers. Carrickmacross, for example, was built to house 500 people in 1841, but within ten years, over 2,000 men women and children were crammed into the buildings. It’s no wonder disease spread easily here, until even the poorhouse dead were not welcome in public cemeteries and had to be buried on-site in mass graves.

The girls’ dormitory at Carrickmacross, with raised platforms where girls slept head-to-head

The girls’ dorm today

So, how did this all happen? was my first question, as I surveyed one of the dorms that has been preserved at Carrickmacross as a reminder of the Workhouse’s past. How could a failed potato crop do this much damage to an entire country?

The Great Famine/An Gorta Mór (the Great Hunger)

Until I began talking with some of the historians and curators at Carrickmacross Workhouse, I had never really understood the impact or scope of the Irish potato famine. But after asking a few questions, I began to get a clearer picture of the implications of not only this devastating agricultural crisis, but the economic and social structure that exacerbated it. Yes, there was a potato blight that wiped out potato crops throughout Europe in the 1840s, but it was actually the social structure of the country that was the bigger problem.Millions of Irish tenant farmers, whose only source of income came from working for largely-absentee British aristocrats, had already been living hand-to-mouth after paying their rent and taxes, with little more than potatoes to feed their families. When the potato blight decimated these crops, their primary source of food was gone. In less than 2 years, from 1844 – 1846, 75% of the Irish potato harvest was lost, leaving more than 2 million people starving (25% of the population).

What about other food?

The tragedy in all of this is that even though the potato crops had failed, Ireland actually was still producing plenty of food. Beef, pork, poultry, milk, dairy products, grains and produce were all available despite the potato failure, but these foodstuffs made for lucrative exports and the landowners shipped it to Britain and other countries instead. Landowners got richer, and the poor starved to death.

I was beginning to understand the beginnings of the great rift between the Irish and the British….

Today, there’s a modern art quilt hanging at Carrickmacross that serves as a creative reminder to visitors that although the potato crops had failed during the Great Famine, Ireland had no shortage of other foodstuffs.

This quilt shows the other foods grown in Ireland but exported (in colour) during the Great Famine

Emigration: the Poorhouse Alternative

The Potato Famine was the impetus for another mass export, too – people. Faced with alternatives like starvation or the Poorhouse, many Irish farmers were offered cheap or free passage to emigrate to other countries. More than 1 million desperate people headed out for America, Canada, England and Australia, booking passage on whatever ship would take them.

“The survivors of the famine and the pestilence have fled to the sea-cost and embarked for America with disease festering in their blood. They have lost sight of Ireland, and the ships that bore them have become sailing coffins…”

Thomas D’Arcy McGee, 1848

Sadly, thousands of these people died on ships that were poorly provisioned and overcrowded, conditions that encouraged the spread of disease on what became ‘coffin ships’. More than 100,000 sailed to Canada alone, but with a mortality rate of 1 in 5, the crossing took a terrible toll.

Earl Grey’s Pauper’s Emigration Scheme or “How Orphaned Girls Were Shipped to the Colonies”

38 Orphan girls were shipped off from Carrickmacross to Australia as servants and brides

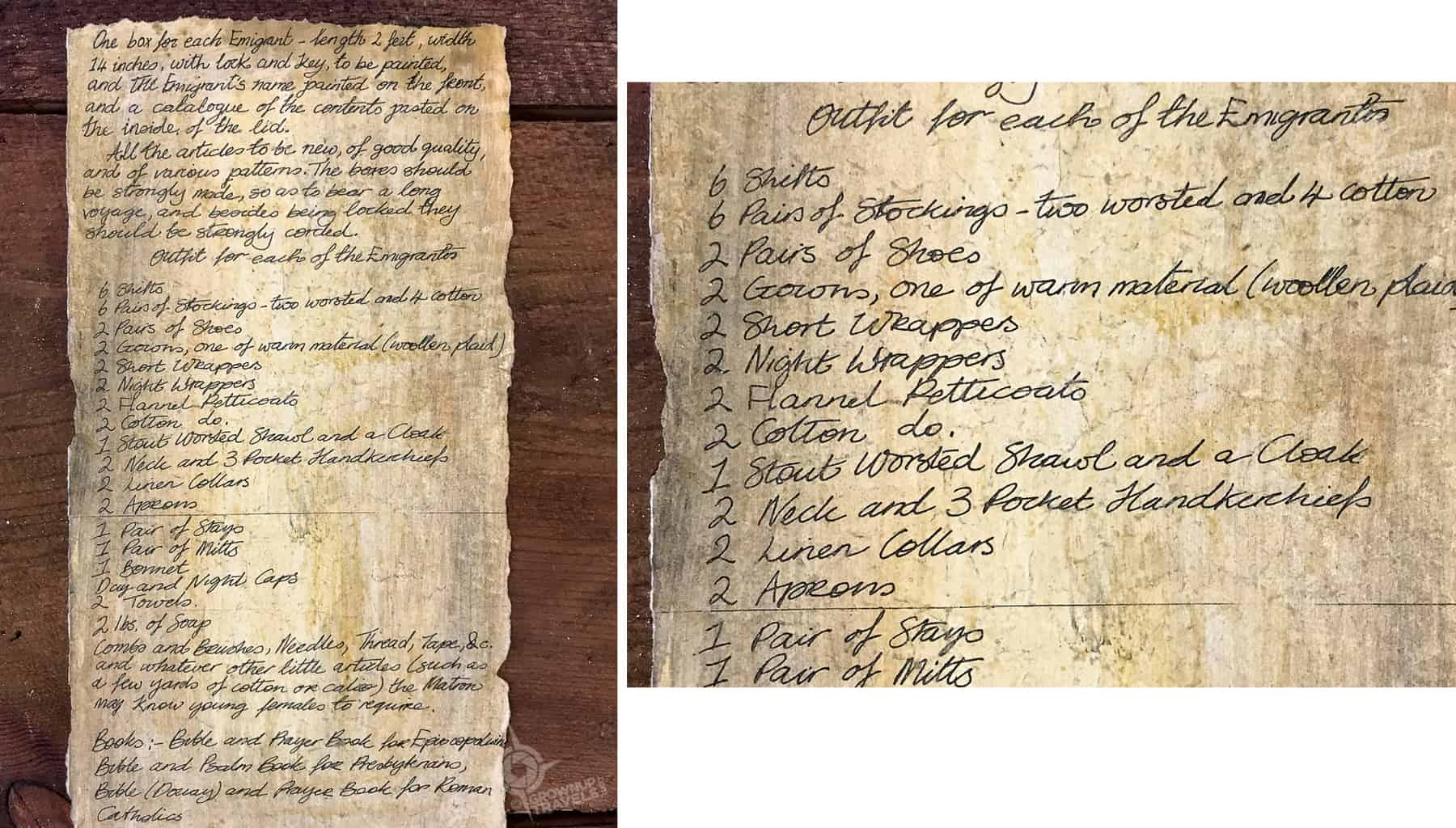

Starvation had taken its toll on Poorhouse families as well, leaving thousands of orphans under the care of the Workhouses, and another plan was put in place to place these children abroad: the Pauper’s Emigration Scheme. This plan was developed by Earl Grey, and resulted in more than 4,000 girls between the ages of 14 and 18 being shipped off to Australia as servants and/or wives. Carrickmacross Workhouse’s records identify 38 young girls who were sent off to Sydney and Adelaide, equipped with a trunk of clothing.

Today there is an art installation in the former girls’ dormitory at Carrickmacross that pays tribute to these orphans, including an example of the ‘dowry’ trunk that would have accompanied each girl on the journey and an itemized list of its contents.

Art installation in the girls’ dormitory commemorating the orphan emigrées

Orphan girl’s ‘dowry trunk’ contents

The cruel irony is that these girls had never seen such a wealth of possessions in Ireland, but in an effort to make them appear less destitute when they arrived in Australia, they were shipped off with clothing to suggest they had come from better circumstances.

Carrickmacross Workhouse Today

Carrickmacross is one of the few original Workhouses remaining in Ireland today, as many others were abandoned after the system was abolished in 1920. Even before then, many of these facilities had evolved into homes for the marginalized in society; the poor, the elderly who had no one to care for them, or homes for unwed mothers, adding to the stigma of their poorhouse past.

So it was actually encouraging to see that Carrickmacross has found a way to both preserve its past and contribute to the future of its community: after being restored in 1990, this former Workhouse now offers guided tours of their Famine Museum and restored dormitory, helping to educate visitors like myself about its history. And the modernized space also provides meeting rooms and offices for a dozen or so social agencies and public service organizations that serve the town. I found it particularly fitting that the facility that once housed poor children and orphans now includes a day care centre for the town’s residents. And they even offer help with genealogy queries, if you are looking to locate your ancestors who may have come from the area.

Sidenote: Sting’s great, great grandmother, Mary Murphy, actually died here at Carrickmacross in 1881, and Sting paid a visit here in 2015 after a Belfast concert.

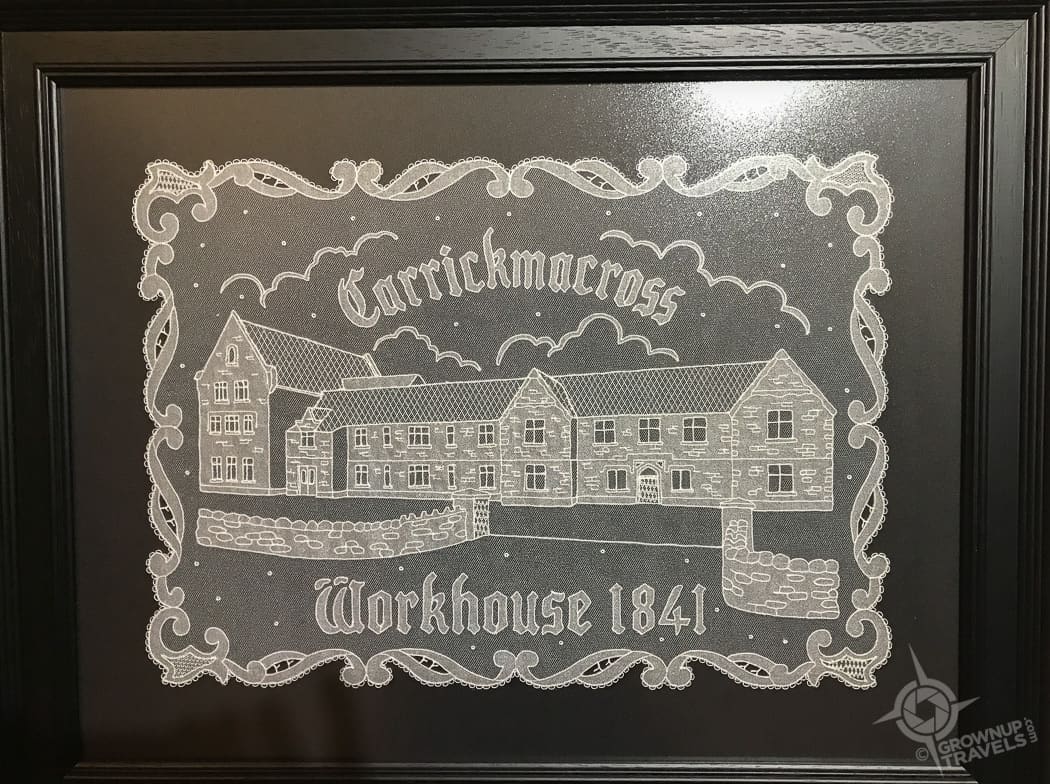

But there is also another legacy of the workhouse that has played a role in Royal Weddings since the 1800s: Carrickmacross Lace.

Carrickmacross Lace: Another Workhouse Legacy

Carrickmacross lace is renowned in Ireland and Britain

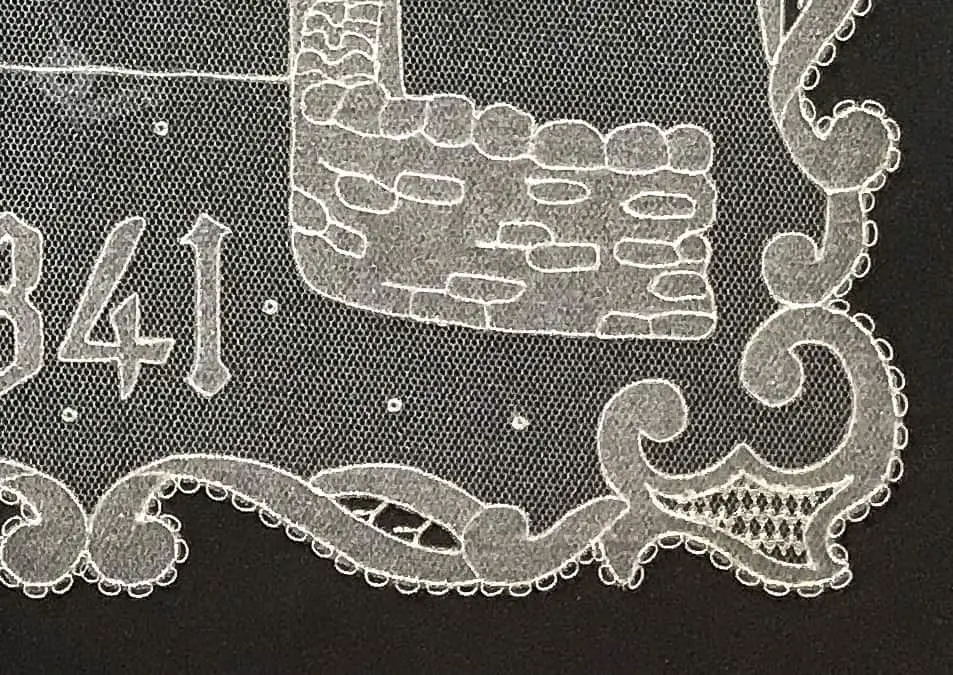

One of the few beautiful things to come out of the Workhouse here at Carrickmacross is their signature lace, first taught to the women of the workhouse in 1849 as a way to generate income from the female workers. Known for its signature looped edge, embroidered ‘thorn’ detail and cutaway organza, Carrickmacross lace came to the attention of Queen Victoria who commissioned a piece for her son, Albert, in 1850.

Looped edges, embroidery and cutout organza characterize Carrickmacross lace

Since that time, every Royal Bride has worn a piece of Carrickmacross lace, including Princess Diana, whose sleeves were trimmed with it, and even Kate Middleton’s lace bodice was created using the same signature Irish technique. Today there is a framed piece of specially-commissioned lace at Carrickmacross that was created in 2014 for the Workhouse.

This piece was created in 2014 and hangs in Carrickmacross

This 8-inch piece of Carricmacross lace with rose design was available for 73 Euros

A Poorhouse, Yes, But Rich in History

While visiting a poorhouse may not seem like the typical thing to do when travelling, my visit to Carrickmacross Workhouse was an historic and socio-economic eye-opener. Not only did it give me a better understanding of Irish history, but it also gave me context for an expression that I’ve used for years without really understanding its cultural significance.

And isn’t that one of the reasons why we travel in the first place?

Special thanks to Tourism Ireland, who hosted me on my visit to Carrickmacross.TIP: Carrickmacross Workhouse is located in County Monaghan, about 1 hour from either Dublin or Belfast. Guided historic tours are offered daily Monday-to-Friday for 6 Euros per adult. More information can be found on their website.

I have to admit that I didn’t know the history of the Irish potato famine. It’s ironic that history often repeats itself in heartbreaking ways. Royalty and rich folks made more money than ever as people around them died. Thanks for providing all the background and history.

I didn’t know the real history either, Sue. Which was a real eye-opener for me and made sense of a lot of the ‘Troubles’ that followed.

Very interesting. I think visiting places like these should be a typical tourist thing. They help provide better understanding on so many levels. They also make us think about how we are treating people today. By the way, that lace is absolutely beautiful.

I guess that would depend on how ‘deep’ a traveller wants to go when they visit a place. For many people, it’s just about seeing the sights, which means they miss out on some of these moments. I know that this particular visit really stuck with me in a way no visit to a monument would.

I so hope this inequity is never repeated. Until you pointed it out I had no idea there was plenty of food but it was exported. Incredible! Horrific. So wrong. Yes, I can see how the ‘troubles’ began.

I agree. I was surprised to learn that there was an abundance of food during the Famine – just not available for the poor.

terrific article. that is one of the key reasons I travel. to understand parts and pieces of history and what it means to us today.

I couldn’t agree more, MJ. Every time I go anywhere, I feel like I am learning history for the first time (I must’ve been ASLEEP in school!!) 😉