Cross in the Convento do Carmo ruins

It was one of the most significant days of worship on the Christian calendar, All Saints Day, a morning when almost the entirely-Catholic population of Lisbon found themselves inside churches and cathedrals honouring the Saints who had died and entered Heaven. Little did these Lisboans know that 50,000 of them would soon be counted among the dead themselves, following one of the most horrific natural disasters in human history: the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755.

Ruins of St. Nicholas church by Jacques Philippe Le Bas 1757

Largely uneducated, and completely ignorant of any of the science of seismology, the residents of Lisbon were unprepared for what must have seemed like the wrath of God himself. What else could explain the fact that on one of the holiest days of the year, the city’s greatest churches trembled until they imploded, showering tonnes of wood and stone onto the congregations gathered within their halls, terrorizing worshippers and crushing them where they knelt. Was it punishment for Portugal’s sins against the people it had conquered and the new worlds it had exploited since its Age of Discovery?

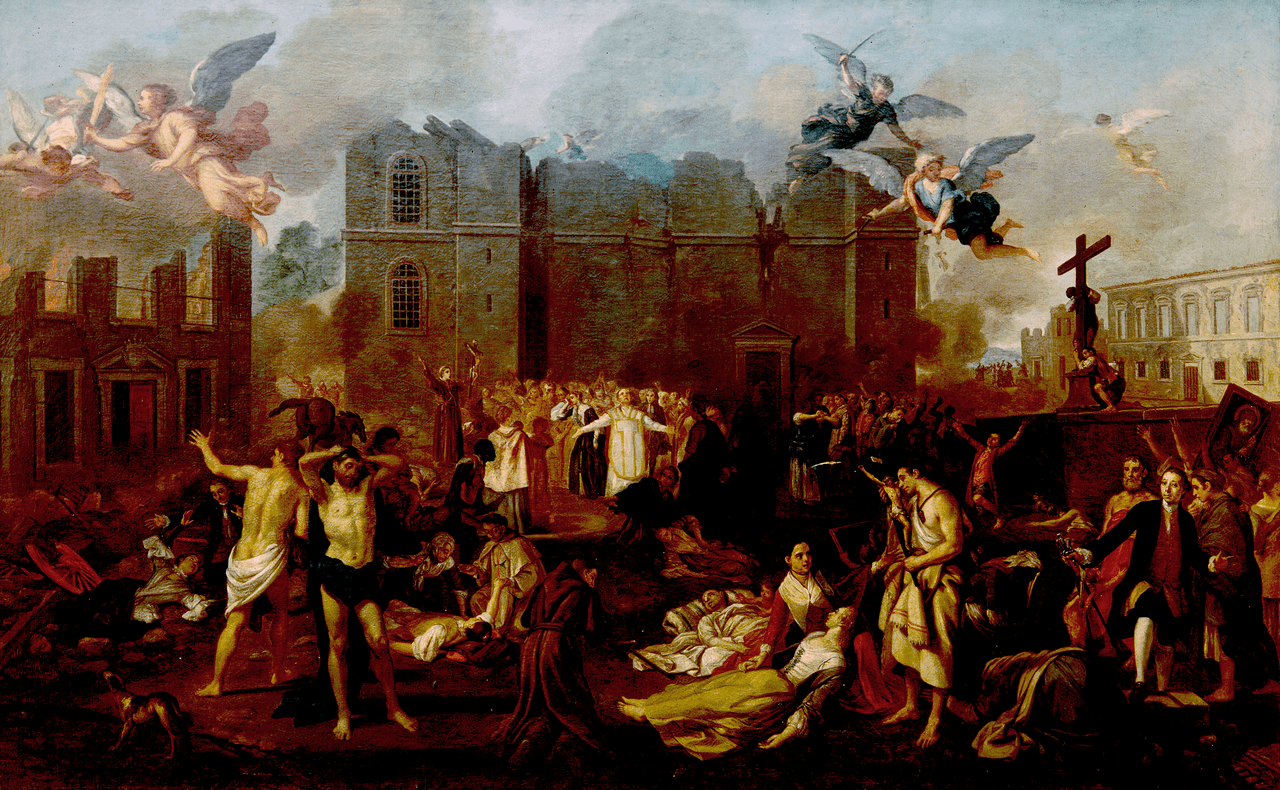

Joâo Glama Stroberle painting of Great Lisbon Earthquake

For what must have seemed like an eternity, three tremors rocked the city in the space of 10 minutes, the second quake lasting for more than 3 and a half minutes and measuring almost 9.0 on the Richter-scale. Survivors who hadn’t been crushed or swallowed up in the giant fissures that opened in the streets fled to the shores of the Tejo river, hoping to escape the crumbling buildings by seeking safety in the harbour’s open spaces. But the open space that greeted them was the riverbed itself, exposed after its waters were sucked out to sea in a reverse tide that we only now understand would soon spell disaster: tsunami!

Part of a massive tiled panorama in the Azulejo Museum showing Lisbon and its harbour before the Great Lisbon Earthquake

Forty minutes after the first tremors rocked Lisbon, a giant 12-metre high wave crashed onto the shores of the city, destroying not just the harbour but the thousands of people who had fled the city streets for the safety of the river. Two more waves hit the shore, dragging people and debris out to sea and capsizing boats filled with more people desperately seeking refuge from the city. But even this was not the end for the survivors who remained, as they would face yet another disaster, as fire swept through the devastated city, raging for 5 days until more than three-quarters of the city lay in smouldering ruins, and a third of the population had been killed.

The remains of the Convento do Carmo, where in 1755 the roof collapsed on worshippers inside.

Before coming to Lisbon for the first time, I had read about this ‘Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755’ in a guidebook, but I had also read about the history of the monarchs, the topography of the city, the best places to eat, and the must-see attractions – all of which were just words on a page with little human or personal context. Like the steepness of the city’s hills, none of it became real until I actually began walking the city. In fact, it was while Henk and I were on a walking tour that one of the local guides was able to put this apocalyptic disaster into human perspective for me: sitting on the steps in front of what remains of the Convento do Carmo, our guide Pedro described what it must have felt like to be inside the church when its roof began collapsing.

The ruins of Lisbon’s Convento do Carmo seen from the Santa Justa Elevator

Henk and I had already visited the church earlier in the day, taking plenty of photos of its skeletal-like ruins, but listening to Pedro I felt like I was reliving the moment the earthquake struck. And it gave me a whole new perspective on the human toll of this disaster and the hell on earth that the survivors had experienced.

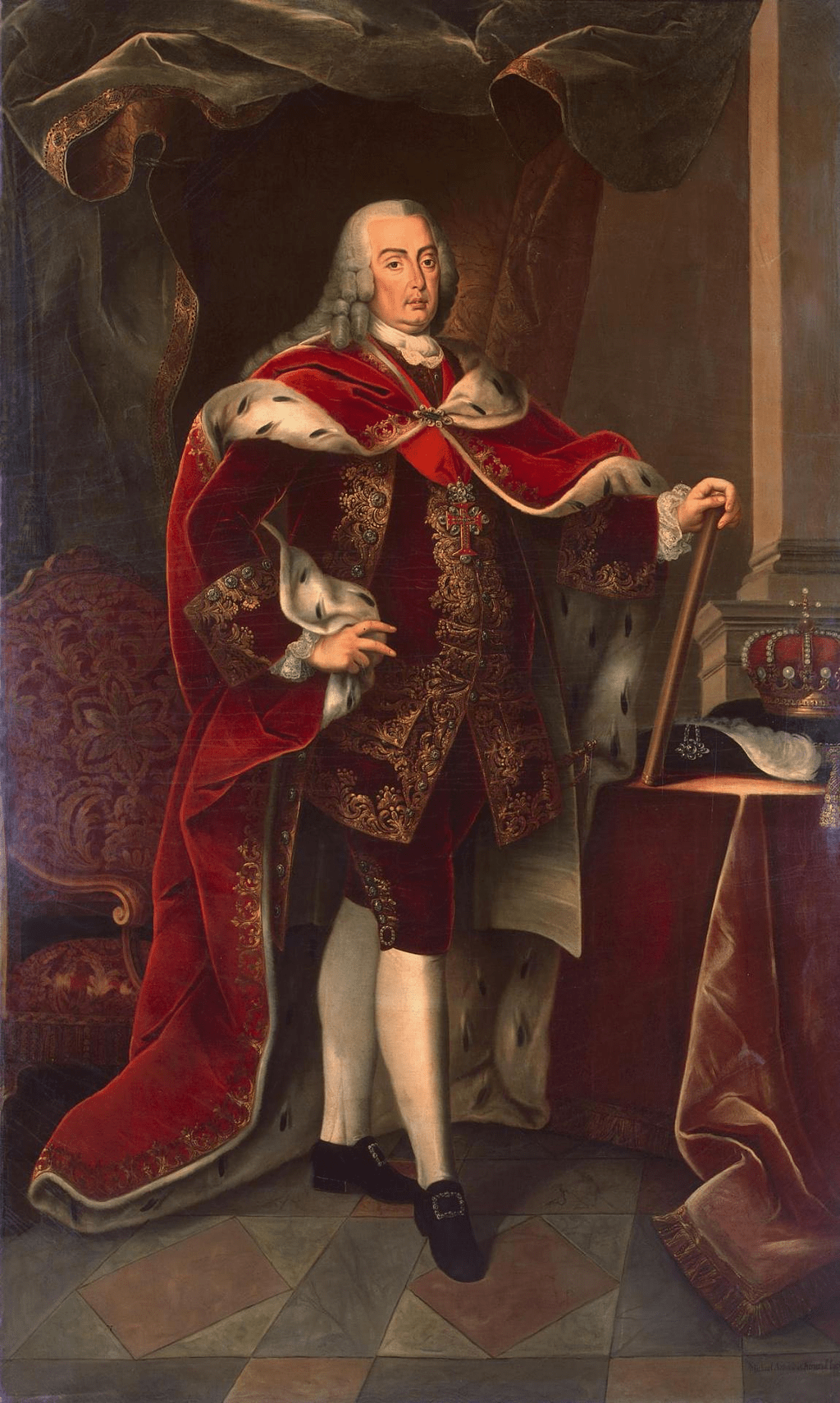

Portrait of King Joseph I of Portugal by Miguel Antonio do Amaral

Now, I could better appreciate the mammoth task of rebuilding the city that was assigned to Pombal; I could understand why finding a building in Lisbon that predates 1755 is so rare; I could even understand why for the rest of his life, King Joseph refused to sleep inside any walled structure, so terrorized was he after having seen his palace – and his city – utterly devastated.

It’s not often that history is made this real, but I think that’s one of the reasons why I love to travel: I never know what will close the gap of centuries, or even millennia, and bring a place and its people to life – or in this case, death. All I know is that the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 is no longer just a date in the history books for me. It’s now one that I will probably never forget.

Rooftops of modern day Lisbon with the river Tejo behind

TIP: We took a free walking tour in Lisbon and want to thank José and Pedro who were our guides, and whose knowledge and familiarity with the city helped bring both historic and modern Lisbon to life for us. If you have the chance when you visit Lisbon, check out these pay-what-you-choose Chill Out tours.

Didn’t know about Lisbon’s Great Earthquake. Interested to know how they got a measurement on this event that predated the Richter Scale by centuries.

I know, I’m curious about the whole measurement thing as well. But I’m guessing they used historical references to it from other countries (probably based on how far away it was felt) to determine the earthquake’s intensity. Now you have me curious…. 🙂

Thanks for the post. It’s true that a being in the right place with a good guide can make the past so real and present.

I agree. I love having guides whenever I travel – it seems like I retain so much more than when I just read about places on my own.

Great piece of history, one we had no knowledge of before. It seems to be a fitting reminder that they chose to leave the convent unrestored.

I was the same and had no knowledge of what was one of the worst natural disasters in history (right up there with a Pompeii). It seems like this one just isn’t shared much in the history classes.

That was a horrific earthquake and you’ve managed to give us an idea of what it must have been like for the people concerned. You, and your guides, have really brought the history to life.

Thanks Karen. I have to admit, this whole piece of Lisbon’s history left an impression on me.

You make history a pleasure to read. Thank you. It’s very well written.

Thank you, but the credit should also go to the guides from Chillout tours. They made it real for me so that I could share it as well.

Fascinating history, what a wonderful way of combining the history, religion and natural disaster to the development of the city afterwards.

I had no idea that Lisbon’s earthquake was so instrumental in all of that city’s development, either. It was a real eye-opener.