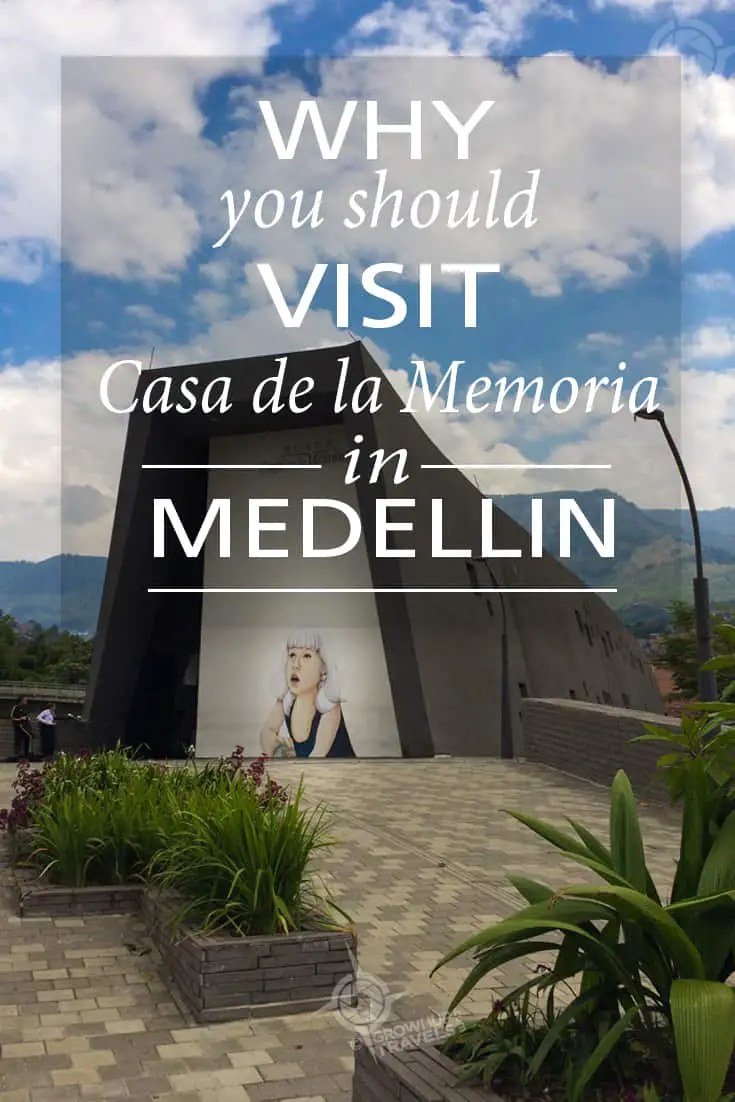

Exterior of Casa de la Memoria in Medellin

There is a saying attributed to the writer George Santayana who wrote in 1905: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Nowhere does this apply more than in Colombia, and particularly Medellin, once ranked as the world’s most dangerous city thanks in part to Pablo Escobar’s infamous cocaine cartel who called this place home. Combine the criminal drug trade with the insurgent guerrillas, paramilitary forces and other armed rebels that have fought for control of the country, and it’s easy to see why Colombia has undergone more internal violence than many nations. Perhaps it is for this reason that the city has built the Casa de la Memoria, so that it will always remember the toll its violent past has taken on its people, in the hopes of avoiding a relapse. It’s also why you should visit the Casa de la Memoria in Medellin, as it will help put Colombia’s troubles into a very human context.

A museum ‘in Memorium”

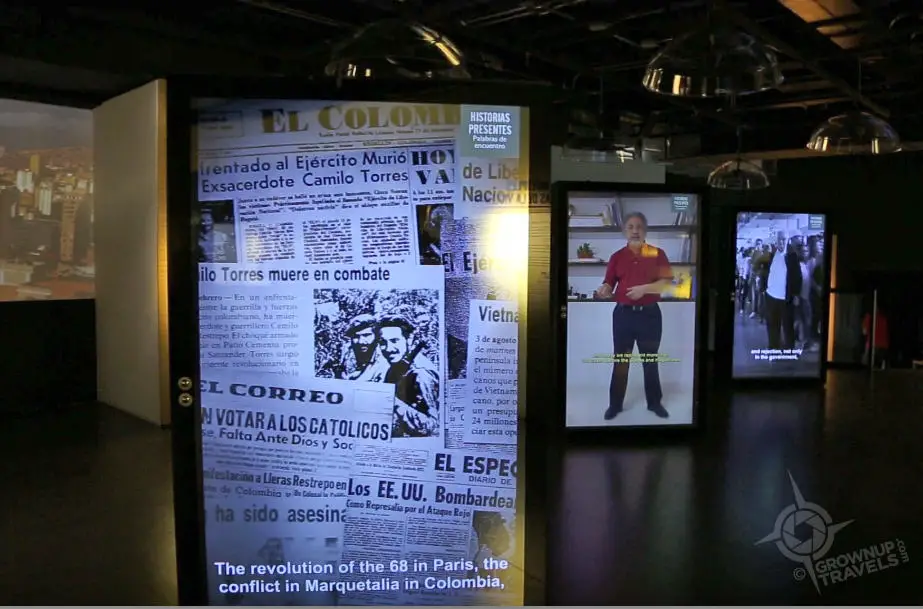

“Museum” might actually be a bit of a misnomer for this building, since this permanent exhibit is more of a memorial than a museum, something similar to the 9-11 Memorial in New York. Rather than trying to explain or document the history of Colombia’s internal conflicts, the Casa de la Memoria exists to ensure that the victims of these conflicts are not forgotten. Videos, letters, testimonials and interactive exhibits give context to the human toll of war, and are powerful reminders of the impact years of violence have had on individuals, families and entire communities.

There are, for example, timelines that show significant events in Colombia’s history leading up to the present, and another exhibit shows the number of murders in Medellin when the violence was at its peak.

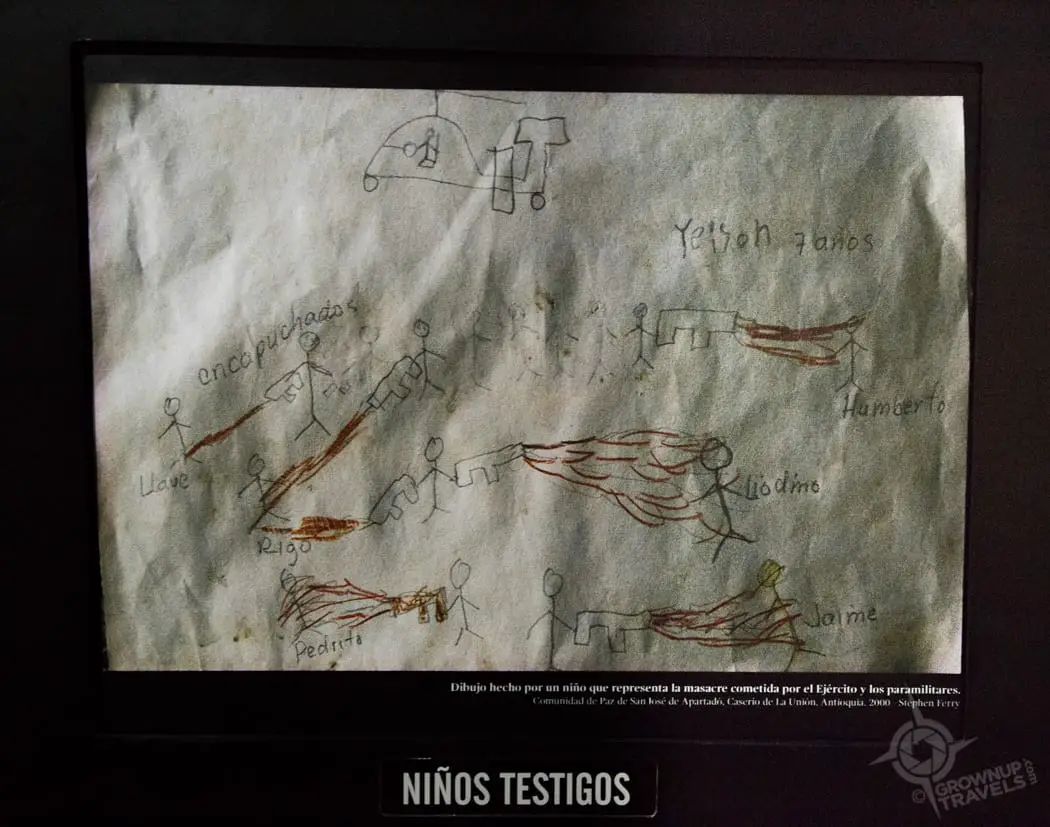

You hear from residents of some of the most dangerous neighbourhoods, who stuck out the darkest years when they were afraid to leave their own homes, but who have remained to see the transformation that has allowed them to reclaim their streets. And then there is the child’s drawing depicting one of the most poignant tragedies in Medellin, when 7 children were killed during an all-out assault on the city’s Comuna 13 neighbourhood.

Black Hawk helicopters were part of the assault that killed 7 children in Comuna 13

There is a room devoted specifically to the images of those ‘lost’ to the violence, whether through assassination, kidnapping and forced ‘conscription’, or literally being caught in the crossfire between warring factions. Entering this dark room is a solemn experience, like walking into the centre of a human galaxy where the stars are photos of individuals that illuminate and then disappear, reflecting a small fraction of the more than 70,000 people who have vanished in the blink of an eye and without a trace. It is a poignant experience for Colombians and visitors alike.

The exhibits are not all negative, however, and there is hope in the Casa de la Memoria, too – hope that is heard in the voices of ex-guerillas who have laid down their guns to search for other solutions; in survivors of sexual abuse who have become healers themselves within their community; and in the art and music that have become the new expressions of change in the city’s poorest communities. Young men like Kolacho are remembered here, too, whose name appears on a plaque in the gardens on the museum grounds. (Kolacho was a musician and artist who inspired youth from the troubled neighbourhood of Comuna 13 to express themselves through street art and hip-hop instead of turning to violence.)

Why visitors should go to Casa de la Memoria

Most of the exhibits in the Casa de la Memoria are in Spanish, and some of the subtleties are undoubtedly lost on visitors like Henk and I. But there are enough testimonials and installations that have been translated into English to make the content easily understood by English-speaking visitors who are trying to grasp the impact of these violent years. What comes through loud and clear, regardless of language, is the suffering that Colombia’s citizens have endured as individuals and as families. It is their desire to emerge from the sorrows of the past that makes this a museum of the people, in the truest sense of the word. This desire for a brighter future is also the reason why Medellin – and Colombia – have undergone such radical, positive transformation in the last decade or so.

Casa de la Memoria is certainly not for everyone, and may not be specifically intended for visitors, but Henk and I were glad we went, as it put much of Colombia’s violent past into a very human context, and we felt more connected to the people who have struggled through these past 50 years. Let’s just hope that this museum serves as a somber reminder of the past so that Colombia’s future will be brighter because of it. Based on our experiences here, it certainly looks like the country is headed that way.

TIP: You can learn more about the Casa de la Memoria and get more practical information on location and hours of operation on their website, (but note that the site is only in Spanish).

What a dramatic way to remember the past and offer hope for the future. Columbia has come a long way from that dark time. I would certainly visit Casa de la Memoria in Medellin if given the opportunity.

What an extraordinary exhibit to remember the past!

Certainly with 50 years of violence, there should be something to commemorate the toll this has taken on Colombia. I think it’s an important step towards putting that in its past. Let’s just hope it truly becomes a museum of things that no longer are happening.

Casa de la Memoria sounds like a fascinating and important landmark within Colombia. It’s encouraging to know that if Medellin can realize such positive transformation that other countries in South America and especially Latin America, also have hope.

I agree. Colombia is the poster child for changing things that many people believe are out of their control. It’s a lesson for all of us.

I hope to return to Colombia later this year, and would like to go back to Medellín. I don’t think this was open when I visited in 2011, but I was impressed with the new-ish music hall and convention facilities. Thanks for posting.

Henk and I were really impressed with Medellin, Kristin, and spent two weeks there. I’m not sure when this museum opened, but it is very new, and seems to be a testament to the city having turned a corner. We had taken the Comuna 13 walking tour previous to this museum visit, which also helped to put some of the violence into perspective, so I would definitely recommend that tour if you do go back.

Thank you for sharing your experiences at this Museum. One of these days I will travel to Columbia. Is it safe for a woman to go alone? I am bilingual in Spanish and English and have no problem traveling in other Spanish speaking countries.

Thanks for your comment, Carol. As to whether Colombia is safe for solo women travellers, I only know from my own personal experience that on two separate trips, we never saw anything that suggested this country was a risky one for women travellers. But common sense would suggest that you do some homework as to where you will be going specifically, and of course, with your language skills, you have an advantage that many other travellers don’t. I think Colombia is an amazing destination with everything it has to offer, so definitely consider it!