One of the most famous horses ever painted is by an unknown artist on the Lascaux cave walls in France

I have never been to either the Lascaux caves or the Chauvet caves in France.

And apparently, I never will.

Discovered more than 50 years apart, in 1940 and 1994 respectively, these two caves have several very important things in common: both are sacred, ancient sites dating back tens of thousands of years; both contain some of the richest cave drawings and most important prehistoric art ever created by man; and both caves have been recreated in painstakingly-duplicated exhibits using the most advanced 3D technologies.

Why the elaborate copies? The reason is because sadly, these caves share another characteristic: along with being declared UNESCO World Heritage Sites, both have also been declared strictly off limits to visitors. Meaning the only option I will have to view these marvels and appreciate their historic and artistic significance will be to settle for the simulations.

But can these fakes really deliver the experience visitors want?

There are arguments that these reproductions of the original caves are more than just meaningless copies – they are an insult to the artists who created these masterpieces. No one in their modern mind would suggest doing the same thing with a Rembrandt or a Da Vinci work of art. Presenting a ‘photocopy’, however accurate, that attempts to mimic the unique talent of these artistic geniuses is devaluing the precious nature of both the artists and the art. So why is it okay to do this with a ‘cave man’s’ art?

Putting aside the argument as to whether or not these replicas disrespect the original artists, the real question to ponder is this: what if just looking at these original masterpieces and taking in their wonder and beauty actually threatened them? What if the very breath these works of art take away from you, once exhaled, spells out a death sentence for them in return?

Since 2000, the Lascaux caves have been beset with a fungus that is creeping over the extremely fragile surfaces of the rock where the iconic images of galloping horses and other prehistoric beasts have survived for eons. This has been attributed to decades of human visitors whose very presence alters the cave’s humidity and atmospheric conditions. Global warming has even played a role, with temperature changes affecting the ‘normal’ circulation of air within the caves.

Worse yet, after several years of particularly heavy rainfall in the early 2000s, horses and stags aren’t the only thing galloping along these rock walls: mold has started to run rampant alongside and on top of these figures. So dire is the situation that global symposiums have been held to come up with solutions, but due to the delicate nature of the rock surfaces, even experimenting with preservation techniques poses huge risks to the original art.

So in the meantime, the caves have been sealed to visitors.

Similar kinds of damage are happening not just in these prehistoric caves, but in other historic sites around the world, for different but equally threatening reasons.

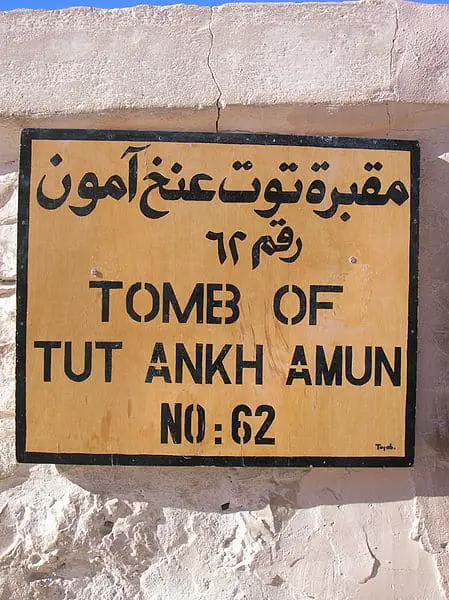

King Tut’s tomb faces similar threats from human ‘moisture’ and bacteria, to the point where the original chambers have been recreated in a replica tomb of their own in the Valley of the Kings, in anticipation of the not-so-distant future when the original tomb will be sealed to the masses.Carelessness by a commercial film crew, while filming an advertisement for a beer brand on the terraces of Machu Picchu, actually damaged a sacred pillar, the Intihuatana or ‘hitching post of the sun’, when a piece of equipment fell on it, leaving a gash in the centuries-old sun clock.

The Vatican, too, is concerned about the toll that visitors are taking on its storied Sistine Chapel, which every year seems to see more and more people packing the crowded sanctuary, ignoring the ‘shushing’ sentinels who are there in an attempt to preserve the sanctity of the chapel. But with thousands of people breathing, sweating, sneezing, coughing or just tromping through the 500 year-old structure, what damage are they doing, beyond just disturbing the holiness of the place? In response to the growing threat these visitors pose, the Vatican announced in October of 2014 that going forward, it would limit the annual number of visitors to the current six million. But that’s still six million people!

So, what is the answer?

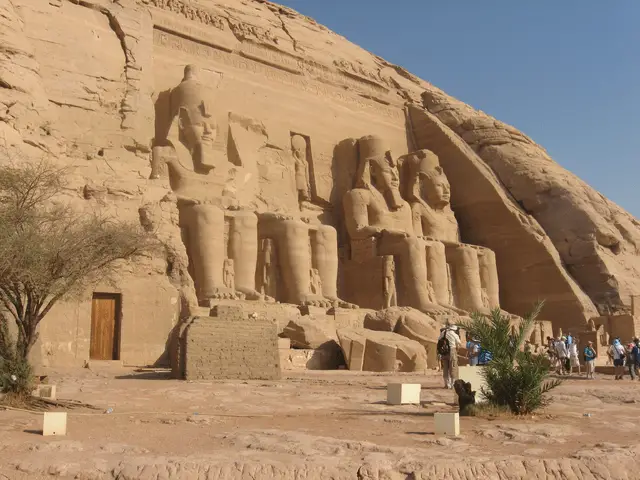

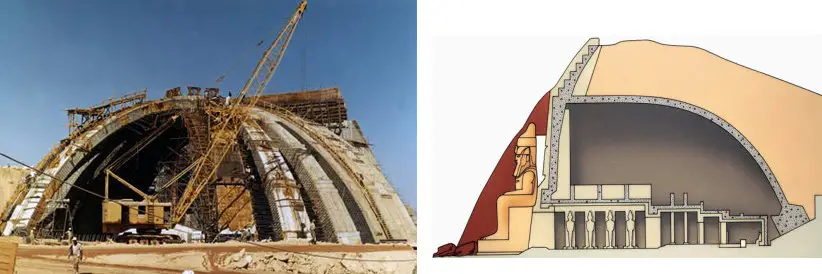

There have been extraordinary efforts done in the past to preserve monuments at risk, Abu Simbel coming to mind. Threatened by the construction of the Aswan dam that would have inundated the temple completely, both Ramses II’s and Nefertiti’s temple structures were carved out of their original cliffside location and moved 200 feet higher up out of reach of the rising waters. There, both temples were rebuilt like a giant 3D jigsaw puzzle inside of a concrete-domed artificial ‘hill’ that simulated the original site, right down to the precise astronomical angle that allowed the rays of the solstice sun to penetrate to the inner chamber.

Some would argue that this is different than the Lascaux and Chauvet replica caves, because the higher artificial structure still contains the ‘original’ Egyptian temples, not copies. From my experience, having visited Abu Simbel, when I walked into the temple rooms, I felt as immersed in the experience as if the temple had been in its original location. And as for the artificial hill itself, I was able to go inside the giant concrete dome that houses these rooms, and look down on the ‘cubes’ that were the temples themselves, but rather than feeling cheated of the ‘real’ experience, I found myself equally impressed by the engineering that went into the ‘fake’ cliff as I was the experience of being in the temples themselves.

I don’t have the answer to the whole replica dilemma. The artistic side of me wants to see the originals, to share the same room or space or tomb where the artists who created their masterpieces hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of years ago, once stood.

The other part of me is terrified by the very idea that these masterpieces might be lost forever because of our own carelessness in how we treat them. It would be a global tragedy to let this human legacy be lost forever, especially if it is preventable.

I have to admit that selfishly I feel an urgency to ‘get there now’ to see these kinds of sites for myself before it’s too late – knowing full well this kind of selfishness comes at the expense of future generations. And therein lies my personal moral dilemma, which I venture to think I share with many other travellers.

What do you think? Would you be satisfied with a fake, however spectacular and authentically reproduced, if it meant preserving the original?

TIP: For a rare glimpse inside the original Chauvet caves (probably the only way we’ll ever get to see it), watch this video shot by the BBC when they were one of the few agencies granted access to the interior.

I was to the Lascaux reproduction cave in recent years. I went disappointed that I was too late to see the real thing. I was pleasantly surprised to see that they had done a very good job with the “fake”. Although not original, it is really worth experiencing. Some things just have to be restricted to preserve them. Having good pictures and videos of the original, along with a chance to ‘almost” experience it, is a reasonable alternative.

So glad to hear, MJ, because as I said, part of me feels like you did, about being ‘too late’. I’m encouraged by the response to this post, because I’ve heard from a couple of people that visiting the replica caves has been a very impressive experience. Thank you for sharing yours!

I think all this lamenting not seeing the “real” caves is a bunch of juvenile nonsense. A typical sense of entitlement. If you want to see “real” caves, study for 10 or 12 years of graduate school and then sweat and suffer the “real” work of an archeologist. Meanwhile, the rest of us can be grateful for all that is being done to protect the ancient work, and for the incredibly beautiful and realistic reproductions. Get a grip.

I think it’s entirely understandable that Lascaux and Chauvet caves would be off limits. Not only are there inadvertent repercussions such as you’ve outlined, but the risk of vandalism and defacement appears to be on the rise. So sad. “This is why we can’t have nice things.”

It’s so true. Not everyone has enough respect for these treasures, and in some extreme cases (like in Syria of late), there’s no way to undo the damage.

Excellent read Jane. Well researched with thought provoking arguments on both sides. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks, Julie. It’s definitely a tricky problem when travellers are ‘ruining’ travel in some ways. At least this provides some kind of alternative, and from what I’ve heard from someone who has been to the Chauvet replica, it’s very impressive.

Thoughtfully written. I’ve been to the Valley of Queens in Egypt which is in the same restricted operation mode, and after seeing the freshness of the pigments because of protection from humidity of human breath, I can see why we should protect these priceless treasures.

I can relate, too, Shila. Twenty years ago, I visited a tomb of one of the artists who worked in the Valley of the Kings, and only a few of us were allowed down at a time, because of the small space and potential risk to the paintings due to our proximity to the walls. I couldn’t believe how incredibly vibrant the pigments were, even after 5,000 years! I bought a postcard to capture the memory, and I’m sure by now, a postcard is the only way most people will be able to ‘see’ the tomb. I look back now feeling alternately privileged to have seen it, and guilty for having contributed to its inevitable ‘damage’ because of my visit.